Of course, as is usual with me on the weekend, I started reading all my open tabs in my browser. And the first one I read was a paper where they crossed two pure strains of mice and correlated microbiome and genome.

“In this study, the BXD population [CS: the first generation hybrid mice] was used to detect and quantify genetic factors that may have a significant influence on the variation of gut microbiota. We have demonstrated that host-genetics is complex and involves many loci [CS: locations on the chromosomes]. These differences in microbial composition could impact susceptibility to obesity and other metabolic traits. Functional analysis of gut microbiota and characterization of the relationships with host-genotype [CS: genotype is the sum total of genes] has important implications to human health and agriculture. The gut microbial composition can be temporarily altered through dietary interventions tailored to host genotype, ultimately mitigating the effects of unfavorable alleles [CS: alleles are variations of a single gene across organisms] and inducing profiles that promote human health. Genetic variants that influence gut microbiota may also be used in selection programs of livestock to improve feed efficiency, disease resistance, and to reduce dissemination of pathogens associated with zoonotic diseases such as E.coli O157:H7 or Salmonella.”

Heavy stuff. We all knew this, but needed the simple scientific example of it. And this is foundational for this science moving forward.

Genetic analyses

So what did they do here? Lab mice are usually pure strains where each individual’s genome is identical. When you cross two strains though, the first generation of progeny are all mixed up in their genetic make up. So in this case, the scientists were able to see a whole range of variability in the genome and correlate that to the prevalence of different microbes in the gut. The idea is that regions in the genome would be associated with certain types of bacteria being maintained or lost.

Sure enough, they honed in on a region and “uncovered several candidate genes that have the potential to alter gut immunological profiles and subsequently impact gut microbial composition”. The region was rich in immune system genes. Also, these immune system genes were related to things like obesity as well, suggesting a connection with metabolism of food. Note: it’s not necessarily that there’s some auto-immune issue attacking the animal’s tissue, but could likely be that the immune system isn’t supporting the right bugs.

For those of you who know transfaunation as an option for helping resolve IBD: This might suggest that even if you do repopulate the flora of the gut, the host might not be able to maintain the flora, not just due to diet, but primarily due to immune profile.

Cool, isn’t it?

One comment that struck me, which points to the variability in frequency and intensity of IBD: “variation in gut microbiota and complex relationships with host genetics can represent unaccounted sources of differences for physiological phenotypes including susceptibility to obesity.”

But that makes sense.

What does this have to do with Eastern European Jews?

What does this have to do with Eastern European Jews?

I happened to have an animated discussion last night with my wife and another couple, who are close friends (yes, we spent a lot of time talking about “poop” at a restaurant; yes, we’re total nerds). As we were leaving the restaurant, my wife reminded me that Eastern European Jews are know to have a higher rate of inflammatory bowel diseases.

That got me thinking.

And this is pure speculation: Eastern Jews are also known to have diseases that are related to genes in brain development. Folks have suggested that the living and working restrictions of Eastern Jews selected for variants of genes tied to things like increased intelligence (for much of their time in Europe, Jews were restricted to certain more white-collar, brain-centric professions). But as a consequence, while having one of these gene variants was helpful to brain development, having two copies led to severe mental development diseases.

So might IBD be a similar thing where the mixed set of genes conferred some sort of microbial or dietary advantage? And then, having the full set of IBD genes causes the full disease? For example, crowded into cities, might have Easter European Jews been more exposed to city and crowding diseases, such as cholera, typhus, or tuberculosis? What is the prevalence of these diseases in Eastern Jews? What is the lung or gut microbial resistance profile in Eastern Jews and Eastern Jews with IBD?

In short, is there a connection between gut issues (or more likely, gut microbe populations) and the evolutionary history of Eastern Jews (city living, profession and dietary restrictions, and so forth). Might the genes involved in IBD, like the the brain development genes, actually present some adaptive benefit at some level?

Kinda makes one think, doesn’t it?

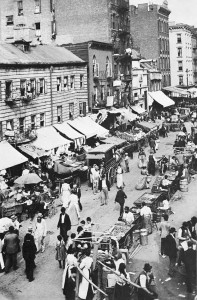

Image from a mouth-watering post on knishes in NYC