I was blessed with an invitation to HealthFOO this year, here in nearby Cambridge. Alas, the event was cancelled due to the intense events after the Boston Marathon.

But not only was I bummed out that I wasn’t going to spend a fun weekend with follow health enthusiasts, but I also had to cancel my Ignite talk.

Microbes!

Of course, I was going to talk about the practical use of microbes. Below, I’ve written what I was going to talk about, with the sides I was going to use. (No, this is not my verbatim script, so it’ll not be exact to the timing usual of an Ingite talk)

Enjoy.

Hello, my name is Charlie Schick. By day, I work for IBM as a sales consultant in healthcare and life sciences. By night, I am a fermentos, a practitioner and promoter of the practical use of microbes.

Tonight I want to welcome you to the Post-Pasteruian Age. But, for some historical perspective, a Post-Pasteruian Age suggests two preceding ages. Let me tell you about them.

When we think of the Pre-Pasteurian age, we think of a scary time of plagues, food poisoning, death by simple infections, and poor public health systems (can you say miasma?).

But it wasn’t all the bad.

Folks were using bugs practically, for food safety, mostly. Most cultures were fermenting foods – milk, vegetables, grains – to preserve them and improve nutritional value.

Indeed, microbes can be credited for the start of civilization. The magic that converted a warm mash of grains into a well-preserved intoxicating food drove humans to settle down to ensure a steady supply of grain to ensure a steady supply of intoxicant.

Then Pasteur and gang came along.

Hello, Pasteurian Age.

John Snow (upper right) figured out crucial pieces of germ theory. And leading scientists gave us anti-microbial terms like Pasteruization (Pasteur, upper left) and Listerine (Lister, bottom right).

Science!

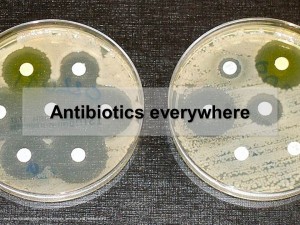

The progress of science also led to Fleming’s accidental discovery that microbes (fungi) themselves were good at killing bacteria, setting us on a long path of conquering microbes through antibiotics.

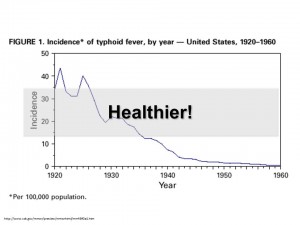

And we can’t deny that we’ve we’ve become healthier overall. Vaccines, antibiotics, public health, food safety have all been components of our improving health, increased longevity, and reduction in microbial deaths from childhood to old age.

But what have we wrought?

Enter the Pasteurian Age! An age of disinfectants at every turn, on every surface, in every process.

But this age is now an age of sterile, processed food. This isn’t the real cheese.

And this age has led to a reduction of biodiversity in our environment, foods, and, most importantly, our bodies.

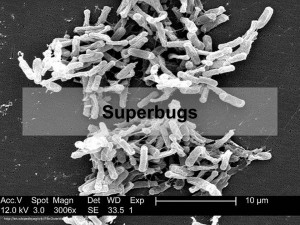

And the only things that can survive this harsh aseptic environment are the super bugs – bugs that have learned to resist every tool we can throw at them to eradicate them.

MRSA, XDR-TB, C diff – you know it’s bad when non-scientists know what these bugs are and what havoc they can wreak (sometimes first-hand).

And our ability to keep our environment so clean is thought to be leaving our immune system with nothing to fight. The thought is that our immune system has turned against us in boredom and is causing a rise in allergies.

But it’s not all bad.

We are now entering a Post-Pasteurian age where there’s a resurgence in the practical use of microbes based on biology and technology and science.

*by the way, I got the term Post-Pasteurian from MIT anthropologist Heather Paxson, in a paper on the US politics of raw-milk cheese.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Sandor Ellix Katz’s amazing paean to fermentation: “The Art of Fermentation”. It’s a celebration of experimentation, chock full of stories and recipes beyond the usual yogurt, beer, cheese, and sauerkraut.

And fermentos (a term I picked up from the book) talk about the bacterial terroir, the mix of native bacteria that is used to naturally ferment foods, as contributing to the final product. Much like the vinyard’s terroir contributes to the flavor of the wine.

And you know there’s a resurgence of microbes in daily living when you see probiotics getting to be vogue. The idea behind probiotics is that competition of good bugs can put the bad bugs in check.

Ok, so some of these claims might now hold up in a clinical trial. But look at the creativity of these vendors. For example, if there are now vagina salves, how soon until we have armpit or acne salves?

Indeed, I’ve played with some of these probiotic supplements that are purported to have therapeutic effect. I didn’t make vagina beer (beer with the right yeast to control vaginal infecions), but I did make a tummy beer (using Florastor on left) and tummy yogurt (using VSL#3 on right).

If you need to know, the tummy beer was yummy. The tummy yogurt wasn’t so tasty, possibly due to the not having a full complement of a yogurt culture.

I also see an increased interest in extracting value from biowaste. For example, dairy farmers are turning into electricity suppliers, learning the art of anaerobic digestion. And municipalities are realizing the value of compost (and the reduction in landfill needs) for recycling all the biowaste we thoughtlessly throw away.

And there have been huge changes in microbiology. It feels to me a total rediscovery of the wonders of microbiology. Technological changes in gene sequencing and analytic algorithms have led to a growth in microbial ecology studies – in the environment and, most importantly, on our body. For example, we are trying to see patterns in what microbes individual carry while healthy or sick.

And this understanding can lead to bacterial cures, cures where bacteria are applied to restore microbial function in the patient.

For example, in whole bowel transplant for bowel inflammatory diseases. It was found that leaving the donor’s microbes intact rather than flushing them out led to better outcomes.

Another popular example, Clostridium difficile is a nasty infection, usually acquired in a hospital after a patient has had a course of antibiotics. Current standard antibiotics are not too good at eradicating this infection, leading to a high rate of relapse.

Understanding the ecology of the bacteria in the gut and C diff’s role in this ecology has led to an interesting solution – transfaunation. Or, transferring poop from a healthy individual to someone with C diff.

Initial tests have been promising. And scientists are now trying to better characterize the sets of bacteria that help C diff patients recover.

Welcome to the Post-Pasteurian Age.

It’s an exciting time for the resurgence of the practical use of microbes in food, products, and health.

But don’t be passive in this age. Go out and ferment something!

Overall I really liked your article, and it seemed like the comment about allergies being bored glossed over a rather broad subject. There’s a large number of possible reasons why people develop allergies and wouldn’t it have been better to tie it in with a couple of them. Disinfection, GMO foods, Bacteria ecology disruption from poisoning (heavy metals, pcb, dioxins) and gut borne pathologies like H pylori or C difficil that take advantage of weak immune systems as a result( mentioned later in article) all come to mind.

Thanks for the comments. re: allergies – indeed, there might be many causes for increase in allergies, but this talk was about microbes, so focused on microbe-related issues. It was not meant to gloss over causes of allergies, but to point out something. Indeed, most of the slides in the talk could stand as their own post if gone in depth (perhaps even books!).