Mahek and I have a running conversation on big company meltdowns (mostly in healthcare). For each one, we discuss who was involved (personalities, investors, consumers), what was the promise and hype, what was the disconnect with reality, and what triggered the ‘oh shit, this is krap’ moment for all.

and I have a running conversation on big company meltdowns (mostly in healthcare). For each one, we discuss who was involved (personalities, investors, consumers), what was the promise and hype, what was the disconnect with reality, and what triggered the ‘oh shit, this is krap’ moment for all.

Of course, at the top of our list is Theranos. But there were other companies who claimed big, grew fast, became famous, and then bombed.

Is this just failure to deliver or is there a more insidious problem at work? Erin Griffith wrote an insightful article on fraud in Silicon Valley. She writes about a long list of companies who took investors along for a ride, with a mix of bluster and swagger, often with catastrophic side effects to the industry and the people invovled.

And part of me wants to believe that it’s deliberate fraud. But I like to give the benefit of the doubt, and think that what comes into play is a wishful thinking that then gets locked in and forces the company to claim the wishful thinking is true. Kinda like a white lie turning into a smoking black grease of a lie that sticks to everyone and everything and can’t be removed.

I’ve seen it up close.

An antidote to this potential fraud is actually proving your solution works as advertised. No, it’s not enough to have customers, as they can also be hoodwinked by the hype; keep in mind Theranos had a customer: Walgreens, not shabby. No, it’s not enough to have good funding; Theranos had solid funding, though from many folks with no experience in healthcare. No, it’s not enough to have your own secret data proving it works, you need to be able to show it to others, transparently.

In short, the proof of the pudding is in the tasting. If no one can taste it – you get what I mean.

Prove it

Lisa Suennen, who has a good eye for healthcare investments, wrote a great article on health startups declaring:

“the digital health theme for 2017 should be: you show me the evidence it works, I’ll show you the money!”

In the article she points out the trends in health investment (less dollars for more companies), consumer trends (not favorable), and the value these health companies have provided investors (still to prove).

One area she discussed revolved around there being so many companies trying the same thing:

“I would love to see a lot less of companies that are “me too” and a lot more of companies with unique solutions to underserved problems.”

I have often mentioned that folks are focusing on the big three (obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular health) to the exclusion of other areas, such as poverty, access, mental illness, and addiction. How many fitness band companies can the market support? And why is it that none of them are making any headway?

But the article on the whole is about how investment in healthcare gadgets has seemed to be about claims and shiny devices, with little proof of effectiveness.

“I think that the convergence of IT and healthcare is here to stay and the trick is making it useful not cool. Trendiness does not equal value. Technology does not equal good.”

“I’d also like to hear some evidence of how all of this big data/AI/machine learning work is resulting in actual activity to change physician and consumer behavior, particularly around improved diagnoses and avoidance of medical errors. So far most of the talk has been about technology and too little of the talk is about results.”

Creative distraction

Eric Topol, a big booster for the use of digital tools to transform medicine, actually has a healthy dose of skepticism when approached by companies making bold claims. In a recent interview, not only does he raise his eyebrows in doubt, but admonishes Forward, a healthcare startup with a coterie of notable investors, to prove their methods and technology. He was baffled with all the PR glitz and saw some things that just don’t make sense, especially because he basically knows all the tech that’s out there.

“I would be firstly interested in what new tools they are using because are they proven, are they validated, are they well-accepted, and moreover I am particularly interested in publishing results to show that this gadgetry is helping these people,” he said.

What’s interesting to note, is that in the article, he also mentions his ‘prove it’ he gave Theranos’ Holmes when she approached tested him. He was impressed, but pushed her to do a head-head comparison with established tests.

“If you want to be an outsider and be a disruptor of healthcare you are still held accountable to the same standards of ‘You got to prove it.’ One of the things is that if you have technology that’s not proven, everyone assumes that it’s harmless but it could actually be harmful when you get incidental findings or if you come up things that are not true.”

Put the lime in the coconut!

I claim that none of this is surprising. Investors partly have wishful thinking. But also, they partly have no idea what they are investing in.

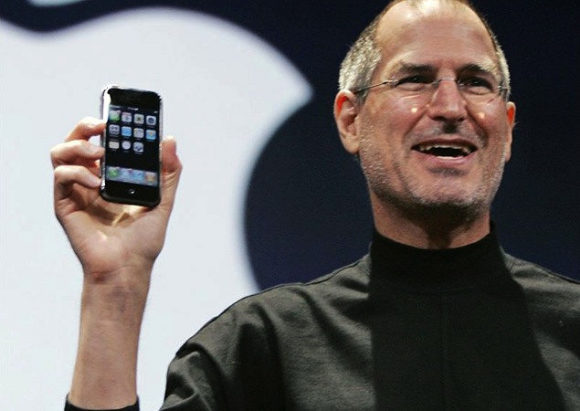

Theranos had that ‘maverick’ Jobsian feel to it, trying to disprove that “only good science, led by medical professionals, backed by data and able to withstand review by outsiders, can succeed.” At some level, that is true. I don’t think you always need medical professionals (don’t flame me). But you always need good science. As this article is kind enough to note through comparing Theranos’ go-to-market strategies with two others, you need to show evidence! Prove it!

If you are going to claim that your baby monitor catches SIDS, then it better. No wishful thinking can change the truth. And you are putting a lot of children at risk. Oh, someone already did this and the FDA isn’t happy.

If you’re going to be used by folks making sure they are not too inebriated to drive, you better be accurate. Oh, someone screwed up and is being punished.

If you’re going to claim that consumers want to measure their activity, you better be able to articulate why someone wants to measure their activity. Otherwise, you’ll not be able to last. Oh, FitBit isn’t doing so well.

Digital snake oil

This sobering reality is not recent. FT wrote about this early last year. And my skepticism with the use of devices in healthcare is well documented, for many years.

Smartwatches, activity sensors, whiz-bang care models that are more flash than substance – this is the new era of digital snake oil and the only way we can get through this is by having everyone transparently prove their value.

Note, I don’t mean to say all of this area in healthcare is digital snake oil (as others have claimed). But we all need to be vigilant and demand proof for every claim.

Let’s make 2017 the Year of “Prove It”.

What do you think?

Image from hirotomo t

All the hubbub around fake news and the presidential elections got me thinking of AIs; how we find, review, and share content (a long term topic for me); how human trust and belief hinge upon millennia-old social strategies. And I’ve read a bunch of articles around how fake news has set off a bunch of navel gazing, soul searching, and finger pointing.

All the hubbub around fake news and the presidential elections got me thinking of AIs; how we find, review, and share content (a long term topic for me); how human trust and belief hinge upon millennia-old social strategies. And I’ve read a bunch of articles around how fake news has set off a bunch of navel gazing, soul searching, and finger pointing. On Jan 9th, 2007, I was in London, at the IDEO offices, sitting in one of their conference rooms with a bunch of Nokians and IDEO-ans. I do not recall if we were streaming the audio or refreshing a page of someone live blogging from the iPhone launch event [Update:

On Jan 9th, 2007, I was in London, at the IDEO offices, sitting in one of their conference rooms with a bunch of Nokians and IDEO-ans. I do not recall if we were streaming the audio or refreshing a page of someone live blogging from the iPhone launch event [Update:  I finally got around to reading

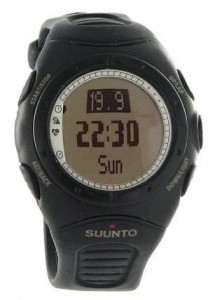

I finally got around to reading  For some reason, discussions of smartwatches make me twitch. Maybe it’s because I got my first smartwatch over 10 years ago.* Maybe it’s because I’ve watched “the next great category” of mobile devices come and go or fling themselves repeatedly on the rocks of disappointment. Maybe it’s because I’ve played with sensors, data, mobiles, and wearables for a long time and have not seen anyone “crack the code.”

For some reason, discussions of smartwatches make me twitch. Maybe it’s because I got my first smartwatch over 10 years ago.* Maybe it’s because I’ve watched “the next great category” of mobile devices come and go or fling themselves repeatedly on the rocks of disappointment. Maybe it’s because I’ve played with sensors, data, mobiles, and wearables for a long time and have not seen anyone “crack the code.” For the past 20 years, I have been helping folks in marketing and sales identify, target, build, and nurture customer relationships, market opportunities, and brand growth. I have either led or heavily influenced sales strategies, marketing efforts, or solution design and development, giving me a unique perspective as to how strategy and execution cut across key areas of an organization and affect their customers.

For the past 20 years, I have been helping folks in marketing and sales identify, target, build, and nurture customer relationships, market opportunities, and brand growth. I have either led or heavily influenced sales strategies, marketing efforts, or solution design and development, giving me a unique perspective as to how strategy and execution cut across key areas of an organization and affect their customers.

I have an ideation game I play called

I have an ideation game I play called  Doesn’t all AI end up being a reflection of who we are as humans? From the practical, I mentioned

Doesn’t all AI end up being a reflection of who we are as humans? From the practical, I mentioned  You know that a tech trend is growing when there are more

You know that a tech trend is growing when there are more